Ortak Zemin

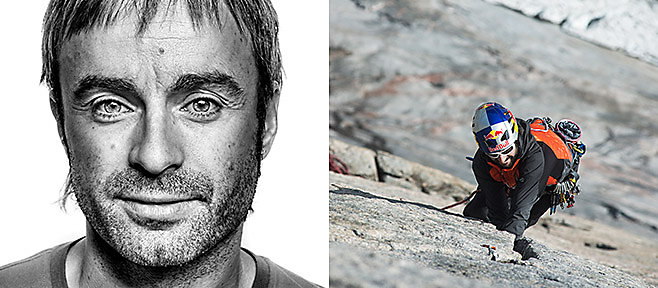

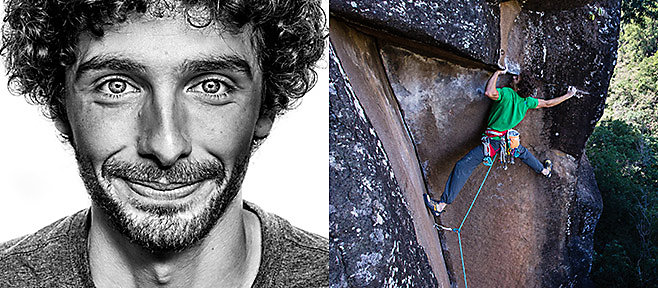

In July 2015, Iker & Eneko Pou, Hansjörg Auer, Jacopo Larcher and Siebe Vanhee ventured into a remote region in Siberia to set-up some new routes on unknown rock. Siebe tells us about the challenges and rewards of this unique trip.

Why Siberia and why that team?

It was brothers Iker and Eneko Pou, two proud Basque old-timers from The North Face team, who came up with the idea to climb in an unknown tundra-region in Siberia. They'd been inspired by pictures they'd seen of the Chukotka walls from an expedition by Australian climbers Chris Fitzgerald and Chris Warners. Because of the big potential for first ascents, the brothers searched for more team members among The North Face's international athlete team. When they asked Jacopo Larcher, Hansjörg Auer and Siebe Vanhee they all jumped at the chance. They knew each other from the international climbing scene and believed the trip would be a lot of fun, with a good atmosphere and an exciting and challenging goal. On top of all that, they would be a climbing team with very different backgrounds, experiences and expertise. Each personality in this diverse international team would bring a unique perspective to climbing into the unknown. So things were clear from the start: the thought of exploring new big walls in a country like Siberia triggered the need for exploration and challenge that was in each and every one of them.

What made you decide to go?

Colourfully dressed, extrovert people like us apparently needed to be brought in for interrogation. That's when the story of endless waiting sessions and Russian bureaucracy started. First of all we dealt with the migration centre of Bilibino. This is where we all got interrogated one by one in the small office of the senior migration officer. I went in first and was placed in front of a big Russian man who looked at me like I was about to steal his wife. A little intimidated I started to explain the reason for our trip and tried to make it clear we were only there for climbing. Thanks to an English school teacher that they called in to translate, I could slowly explain who we were and why we were in Bilibino as tourists. For them it seemed unreal that we'd come all the way from Europe to climb mountains in an - according to them - flat area with just tundra. One by one we went into the office and gave all the information they needed. Apparently we didn’t have a certain permit to enter the Chukotka area and we'd broken Russian law. Not knowing what would be the consequences of our illegal action of entering the area, the police took us to the jail where we had to talk to the head of police. More waiting and explaining followed, but this time they let us go more quickly. After another day of fingerprints and paperwork it was clear we had to pay a fine but luckily they let us stay in the region.

What was the main goal of the expedition?

Like on many of those remote climbing expeditions, the goal was to reach the top of a mountain, to climb a first ascent - several if possible. Because we were a group of five climbers and the walls were around 500m high, we aimed for as many first ascents as possible. Besides having a main objective, the way we would reach it was important to us. We would try to free climb our way up to the top, following the most logical and natural line trying not to leave unnecessary fixed gear. Once in nature, the Pou brothers were aiming for one-push, alpine-style climbs while Jacopo, Hansjörg and I were keen to search for a challenging line that would require more then one day to free climb.

What were your favourite memories?

This was different for all of us - it was the area, the walls, the culture, the mosquitos, the days full of light and the multi-functional team. Climbing in two teams on these walls with an average height of 500m was great. Every possible climbing day the whole team split up in two for their challenges. At the end of the day - which was still light because we were under the midnight sun - we would gather at base camp to cook dinner and share our adventures and challenges from the day. We'd discuss possible lines, ways to approach the climb and climbing styles and ethics - which was a recurring topic at base camp. Coming from different ‘sub’-climbing communities our values and points of view on climbing big walls and exploration were slightly different. Wherever you are, climbing is a social experience and our time in Siberia was no different.

What was the biggest challenge?

Just getting to the climbing area! Travelling through Russia isn’t an easy task. Not many people speak English, definitely not in a remote town like Bilibino where people aren't used to seeing tourists, so communication was tough. On top of that, the cultural differences were pretty big. While we, and definitely the Spanish part of our team, are more extrovert and open; the Russians are more reserved. At first it was hard to tell to what extent our presence was accepted. Unfortunately, the answer to this question became pretty clear not long after we arrived in Bilibino. Bilibino is a remote town four hours flight from the closest city. In the past many people worked there in goldmines, nowadays people work in the nearby nuclear power plant. As a group of seven foreigners we prepared our 25-days-worth of food supplies in the many small food stores in town with the help of our personal guide Evgeny Turilov. Apparently we weren’t discreet enough preparing our trip and the eyes of the local, as well as the federal, police were on us.

Colourfully dressed, extrovert people like us apparently needed to be brought in for interrogation. That's when the story of endless waiting sessions and Russian bureaucracy started. First of all we dealt with the migration centre of Bilibino. This is where we all got interrogated one by one in the small office of the senior migration officer. I went in first and was placed in front of a big Russian man who looked at me like I was about to steal his wife. A little intimidated I started to explain the reason for our trip and tried to make it clear we were only there for climbing. Thanks to an English school teacher that they called in to translate, I could slowly explain who we were and why we were in Bilibino as tourists. For them it seemed unreal that we'd come all the way from Europe to climb mountains in an - according to them - flat area with just tundra. One by one we went into the office and gave all the information they needed. Apparently we didn’t have a certain permit to enter the Chukotka area and we'd broken Russian law. Not knowing what would be the consequences of our illegal action of entering the area, the police took us to the jail where we had to talk to the head of police. More waiting and explaining followed, but this time they let us go more quickly. After another day of fingerprints and paperwork it was clear we had to pay a fine but luckily they let us stay in the region.

We were happy to leave Russian bureaucracy and head into our more natural environment… the mountains and rock. Although, there was another surprise waiting for us at base camp. This time it wasn’t Russian bureaucracy or any other political danger. It was the many, many mosquito’s that would make life a bit(e) harder. As soon as we got dropped off the mosquito’s were omnipresent. Although temperatures were high, we all wore clothing that fully covered our skin. Our mosquito nets and hoodies were on at almost all times. To our surprise, the mosquito’s didn’t disappear while climbing and the rain didn't deter them. Soon we realised we were doomed to accept the situation and do our best to ignore it.

OK, so what about the actual climbing - what was that like?

The full team started off attacking the east face of The General. While Iker and Eneko attacked the most obvious dihedral system on the right, Jacopo, Hansjörg and I challenged ourselves with the cracks in the middle. That first climbing day in the Chukotka was truly fantastic. We opened two new routes, "Aupa!" (6c, 300m, eight pitches ) and "Wake Up in Siberia" (6b 240m, three pitches & 5+ 70m) in alpine style. Both routes were on great quality rock and didn't need much cleaning for free climbing.

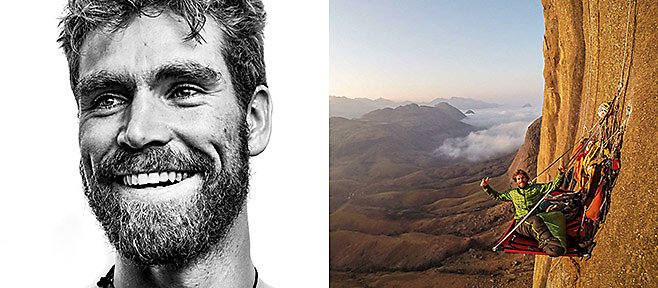

From the day we arrived at our giant playground, The Commander (left wall) caught the eye of Jacopo, Hansjörg and myself. We were eager to search for a challenging line on this steeper wall. From the ground we spotted an obvious red coloured cornersystem halfway up the wall. In bigwall/shortfix style they tackled the wall. Like they had expected, the corner offered them the biggest challenge of the route. After reaching the top of the route they returned to freeclimb the entire line. While Siebe focussed all his energy in free climbing the stemming 45 meter corner pitch, Hansjörg and Jacopo did the same with the upper corner/roof pitch. Despite their first impression of the two corner pitches - they assumed them to be very hard and even impossible because of the small protection - they managed to free climb both pitches on the third day. Overall they only placed five bolts in the entire route, despite the small and not always solid protection. Happy they were having found such a unique climb that challenged them in all possible ways; from getting up (sometimes using aid-climbing techniques), to placing protection, to climbing it free placing the gear. The "Red Corner" (7c+, 450m, 11 pitches) is opened and free climbed by Hansjörg Auer, Siebe Vanhee and Jacopo Larcher in three days time (11-12-14/07/2015).

While the team of three continued to focus on free climbing the Red Corner, the Pou Brothers were on fire climbing one-push routes. They chose a line on The Commander that takes some obvious crack systems leading towards a very wide chimney at the end of the wall. Because of this never drying chimney at the top, the two brothers experienced some wet pitches (pitches five, six and seven), which made them think the wide chimney wouldn't be a good end to a great climb. This is why they traversed out left to find multiple crack systems bringing them to the top. Iker and Eneko Pou created a new route "Into the Wild" (7a, 425m, nine pitches) in one long day of 11 hours and 20 minutes.

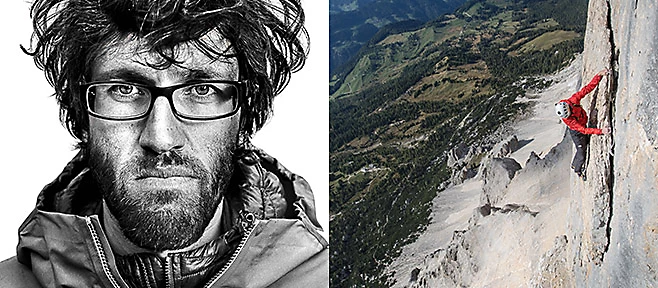

After our team's free ascent of the Red Corner, it was Hansjörg Auer that had the idea of climbing the last unclimbed peak close to base camp. As an experienced technical climber, Hansjörg was attracted by the slabby looks of the pillar on "The Monk". He convinced Jacopo and myself to join him for a quick ascent. We opened the most obvious line in the middle of the pillar which we called "Sketchy Django" (6a+, 400m, seven pitches starting in the gully). This wall had a few slabby sections without good protection, so the "Sketchy Django" of the team, Hansjörg, made some run-outs on peckers and pitons. The rock was amazingly structured with very large crystals, making the slabs easier then they looked. The difficulty of this line is definitely the protection, or lack of it.

"For the ascent of the last two routes of the trip both rope teams struggled with the weather. ""The Two Parrots"" was Iker’s and Eneko’s last route of the trip, which they climbed in one push of eight and a half hours. Although the route was climbed in one push, the Basques had to wait around for two days before the weather allowed them to reach the summit. The line starts on the west side of The Commander and leads into another obvious dihedral, 50m to the right of the ""Red Corner"". The first few pitches were pretty wet and made that section more adventurous. Afterwards the rock was of high quality and they found four incredible and long crack climbing pitches in the big right-facing dihedral.

Our team tackled the left side of The General. We climbed ""From Zero to Hero"" (7a, 490m, 11 pitches) in several days because of the heavy rain that stopped us from a one-push ascent. During the first two attempts we were forced into retreat by a waterfall coming down the face. On the third day the thunderstorms passing through the area took a detour and we didn't get rainded on at all, allowing us to top out on the summit. They were some challenges along the way, notably halfway up the wall at the right-facing corner where it was still wet and hard to protect. Throughout the climb we made use of peckers and pitons because of the lack of better nut and Camelot placements. This climb was one of the most adventurous of the entire trip."

What is the main difference between climbing in Siberia and climbing in more established places?

Adventure! Climbing in Siberia or any other unknown remote place is partly about the adventure of organisation, getting there, hiking your gear into base camp, unknown weather conditions and the search for the most obvious and attractive lines to climb. You have to deal with a lot of uncertainty. When we decided we would go towards the Chukotka region we didn't know much about the rock quality, the amount of potential lines and the weather. If the weather turned out to be bad, we couldn’t go home or to a bar for some beers. Instead we had to wait in basecamp where we read, wrote, discussed and of course… ate. This is all part of the adventure.

To me, it feels very natural to climb a wall and search my way up myself. It’s a lesson in trusting your decisions. In well-known places the routes have already been climbed and sometimes take a line that just doesn’t feel right to me.

For me, it comes down to the way we approach the climbing in a remote place like Siberia that makes the climbing there so interesting. It's not actually the climbing itself.